What Caused the Supply Chain “Crisis”?

Why are container ships queuing by the dozens outside terminals on three continents and retailers apologizing that coveted holiday merchandise may not be on the shelves before Christmas? The ship lines are blaming terminal operators for underinvesting in modern equipment. The terminal operators point the finger at dockworkers’ unions and at land transporters whose failure to move cargo out of the ports is clogging up storage areas. The railroads protest that their own terminals are chock-a-block, knocking cargo owners who postpone collecting their freight because their warehouses are full. Truckers complain about delays at marine terminals and about a shortage of the chassis they need to haul containers, not least because the U.S. government imposed whopping tariffs on Chinese-made chassis after finding that subsidized imports from state-owned manufacturers were harming U.S. chassis makers.

All these explanations, as one journalist commented to me recently, leave the impression of a circular firing squad at work. None of them do much to get at the causes of logistical overload.

So what are those causes? Mostly, well-intended government policies meant to mitigate the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Across much of the world, governments and central banks have pumped money into their economies to keep the pandemic from turning into a depression. Those measures, in general, have been extremely successful: with ample cash in hand and interest rates at rock bottom — British homebuyers can still get a five-year mortgage for 1.04% — consumers have plenty of spending power. But from March 2020 until the past few months, many of the services that households normally consume, from vacation trips to restaurant meals to late nights at a dance club, have been limited by COVID-related restrictions. Unable to buy services, people gorged on goods.

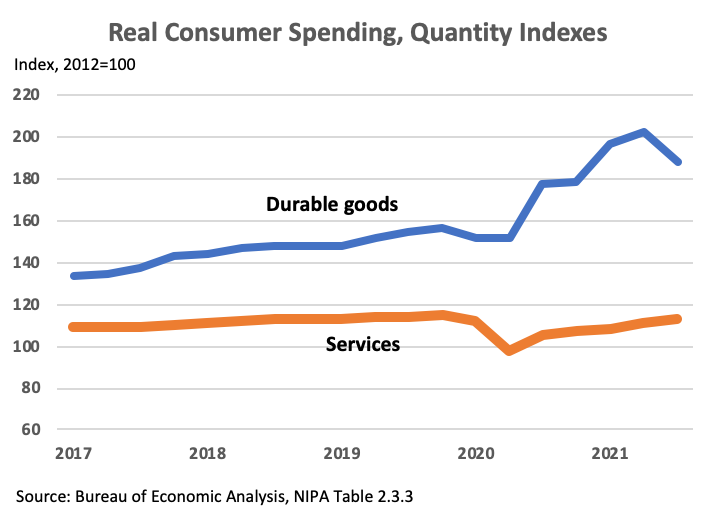

A few days ago, the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis published new data showing how intense this shift was in the United States. BEA’s quantity indexes don’t normally get much attention, but for this purpose they’re useful: you can think of them as measures of the amount of goods and services people consume, rather than their value. The indexes show a trend change in the first quarter of 2020, when purchases of services collapsed, and again in the second quarter, just after enactment of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act on March 27. That law provided for direct payments to families, unemployed workers, businesses, hospitals, and local governments. Almost immediately, consumers went crazy on the sorts of goods that have global supply chains and move in containers, especially durable goods like furniture and vehicles.

Note that BEA’s data show that purchases of durables retreated over the summer, even as purchases of services grew. With the Fed starting to raise interest rates, however cautiously, goods spending is likely to weaken further. As it does, those picturesque queues of container ships will soon be getting shorter.

Tags: COVID-19

Loved the book “The Box”. So informative, and such an interesting history about something that would seem so dull, but is not. Really look forward to an edition that includes some new chapter titled something like “How The Pandemic Broke My Supply Chain”.